Since last autumn we have seen a stream of volunteers coming to Samos to ‘help’ the refugees. It has been a new experience for us although we are aware that this type of humanitarian tourism has been around for some years and is said to be one of the fastest growing areas of the global tourist industry. (Guardian November 14 2010, ‘Before you pay to volunteer abroad, think of the harm you might do’.)

On Samos at least, the term ‘volunteer’ now has a specific meaning referring to those from outside the island who sign up to work with an NGO called Samos Volunteers. The term volunteer for example does not include the many local people who over the past 12 months did so much to support and sustain the thousands of refugees who landed here. Nor does it include the refugee activists who come to work on Samos but refuse to be bound by the rules and regulations of the authorities.

We write about our experience of the Samos volunteers with some care as we are aware that some of our critical observations might be hurtful and discouraging for the volunteers many of whom are passionate about helping the refugees here. It is always been our concern to write in ways which both inform and above all which might benefit the refugees. We make no excuse for wanting to try and make things better by changing the ways in which people think and act. We very much hope that the volunteers will take our words in the spirit in which they are intended which is to think more clearly and act more appropriately when trying to help to the refugees here.

Our Observations and Thoughts

1) The volunteers who come to Samos are very mixed. They are not all young ‘gap year’ tourists although many are students who have just completed some of their higher education. There has also been a significant minority who are older and recently retired. The overwhelming majority are European/North American/Australian middle class Caucasians. We have seen no volunteers from Muslim majority societies and even more surprisingly very few from Greece and none from Samos.

For some, Samos is their latest island. A surprising number can list a string of frontier islands from Lesvos to our north to Kos to our south where they have done some days or weeks of volunteering.

2) Samos Volunteers provides the key contact point and a system for the arriving volunteers. It is an NGO which is part of the network of officially recognised organisations working on the island including the other NGOs and state agencies. It has close ties with the local authority which in the past has provided free accommodation and key resources such as their store house. The downside is that it ties the volunteers into a system that remains part of the problem and not the solution.

3) Many volunteers stay for a very short time, often less than 4 weeks and some for only a few days. They tend to be here today and gone tomorrow. There is very little opportunity for them to engage effectively with the refugees given their stay is so brief. This applies especially to the younger children many of whom have been traumatised by the wars they are fleeing, the terrible journey to get to Samos and then the experience of the Camp. They thirst for stability and safety and many are desperate to learn fully aware that they have missed months and sometimes years of schooling. Many of the volunteers understandably want to work with children but their short stays can be problematic as it exposes the children yet again to a reality which has little stability.

4) We have been surprised by the volunteers’ general lack of curiosity and understanding of the situation they are working in. For example, we can’t recall many asking us about our experiences on Samos and the context here. It is as if it does not matter. They want to do something now. Activity and not understanding seems to be their main concern. Some are very poorly informed and worse, come with negative prejudices especially about young Muslim men which are so widespread in the western media. This week we heard 5 volunteers telling us that the people of Samos are against the refugees. This is not true and insulting to the islanders. Yes, the Samian authorities are antagonistic but not the majority of the islanders.

We suggested to some recent volunteers working in their clothing store that they should involve refugees in managing and organising the place given that the refugees are so stressed by boredom and inactivity. They are crying out to do something. But one responded that she had been warned not to talk to the refugees about the location of the store (which is near to the Camp) otherwise they would raid it and rob it. The volunteer co-ordinator was very concerned when we took a Syrian refugee to the store to choose a suitcase. We had made a big mistake they told us. Refugees were not to come there and certainly not to choose what they needed for themselves. 2 weeks earlier an activist was similarly outraged when she was told she could not bring a pregnant Afghani woman to the store to choose her clothes. We suspect that the rule of keeping refugees away from the store is imposed by the local authority and is a clear example of the kind of difficulties which result from being part of the ‘system’. Nevertheless, the volunteers seem to forget that everything in the store has been sent for the refugees. It is their stuff!

Sadly, many of the volunteers as well as many working for the NGOs here are similar in this respect: they rarely engage personally or deeply with refugees as partners. Some clearly don’t trust the refugees and believe that the refugees need discipline and surveillance when they get near to things they need! Refugees are too often seen as people you do things to even though you may well have no skills or experience yourself. Want to help with the kids? Off you go and do it. It is disrespectful and arrogant and in the main they don’t even think about it.

We have also seen a minority of volunteers behave like trophy hunters such as the 2 young Germans who were here a few weeks ago and did some painting with children. They were with the children for less than an hour (the volunteers wanted to go off to the beach). But still enough time for the kids to make some pictures. Until they were stopped it was their intention to take all these pictures back to Germany and not give them to the children.

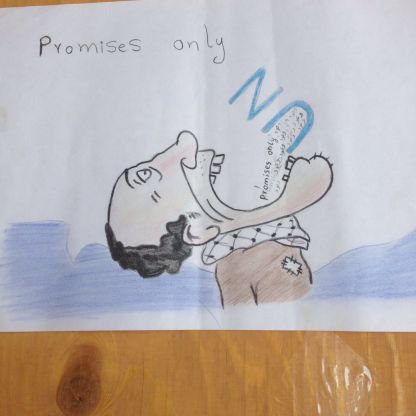

Many are keen for photographs of themselves with refugees which are then posted on their Facebook pages to much acclaim from their friends for being such wonderful human beings. These volunteers want to be ‘the story’. Moreover, as with so many aspects of refugee practices and policies there is no transparency at all with respect to the funds which many raise to pay for their time in Samos. It is not clear to us that this is the best use of resources.

Most of the volunteers we meet have ‘good hearts’ even if their own personal self development seems to be the most important issue for them. They genuinely care. But the refugees need them to have good heads too.

5) There is a general lack of any kind of progressive political perspective on the part of most of the volunteers we have met. Samos Volunteers does not make any attempt to address the political orientations of those joining them. It is as if their assumed compassion is sufficient. Imagine having to confront a 21year old medical student from London who insisted that the Syrian refugees must take responsibility for the destruction of their country? Or who believe that the EU is right to deport them back to Turkey?

The contrast with the activists who ran the 2 Open Kitchens earlier this year couldn’t be greater. These activists worked with and built solidaristic relationships with the refugees. They made friends with the refugees, sitting and talking for hours together. You will rarely see a volunteer sitting in a café with a refugee drinking coffee.

Whatever we might write, we are not going to stop volunteers from coming to Samos any more than the EU is going to stop refugees from coming to Europe. There is rarely a week that passes when we don’t get messages on our Facebook page from those who want to come to Samos. We have no wish to stop them from coming here. There are so many opportunities for them to see first hand the cruelties of the system and hopefully, to use this experience ‘back home’ to press for change.

Overall we don’t feel that volunteers damage the refugees and with respect to clothes distribution they have made a difference to many but it could be so much better for it is not just a matter of what you do but how you do it. Some of their recent educational initiatives also look promising and make good use of the longer times the refugees now spend on Samos.

Concluding Thoughts

The questions we pose for the volunteers are ones we regularly ask ourselves. We don’t always have clear answers especially when we feel we are doing things which should be done by the authorities, including NGOs like MSF, Save the Children, Red Cross ….. as well as the UNHCR. Like government agencies these NGOs hold massive budgets but so much seems to be spent on themselves, their staff, their cars, apartments, meals, logos, offices, mini buses and so on and so on. The idea that this money should be passed on directly to the refugees is never considered and yet in our opinion this would be the most beneficial direct aid for most of the refugees. It would also help more people on Samos as with money in their pockets the refugees would spend it in the local shops and cafés, renting rooms and apartments and even starting their own enterprises here.

We all need to remember that we are not the story. We can never hope to get near to the experiences of the refugees but we can at least try and stand in their shoes and make that the starting point of our activity. It will not be enough but it might mean we can help in ways which shames and highlights the system’s inhumanity to our fellow human beings as well as demonstrating our solidarity and providing something however small which makes refugees stronger and not weaker.